You Defer to AI Doesn't Mean Your Kids Do

What school art programs reveal about who's really passive

Hi there, happy 2026.

At a Swiss AI conference in late 2025, nearly everything I had heard was about how AI would negatively impact future generations, until that evening when Jessica Priebe shared her story.

So I asked her to share it here, hoping to give you a refreshing start to 2026, with hope and new perspectives.

Enjoy

Jing

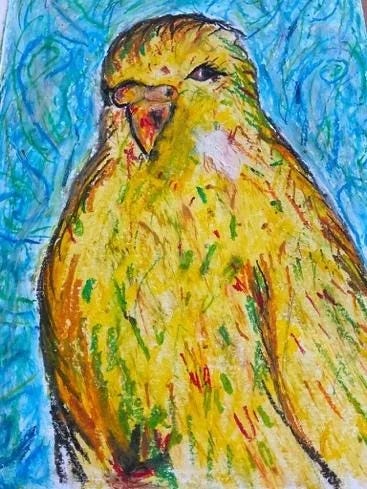

Toward the end of a school art exhibition, I overheard a boy explaining his work to his father. On the wall were two images side by side: a Surrealist-inspired drawing and an AI-generated remix of it.

Beside him, his father glanced at the second image and said, half-joking,

You didn’t make that. The AI did.

The boy did not hesitate.

No, Dad. I made both. And the AI one was harder.

His father looked at him, surprised.

I already know how to draw,

The boy went on.

What I didn’t know was how to make something with the machine. How to prompt it, change the filters, choose which ones were wrong, and which ones were mine.

There was a pause.

Then his father said quietly, “Okay. Show me how you did it.”

That was the moment I realised something fundamental had shifted. The technology had altered the direction of the conversation. The child had become the teacher. The adult had become the learner. And a space between them had opened.

Note, the exhibition marked the culmination of my art residency at the school, where students had spent two weeks learning about AI, developing original artworks, and reworking them using generative tools.

Have your little ones also started to work on an AI project? If yes, what’s your experience co-creating with them? Share the experience!

What An 11-Year-Old Taught Me About Learning With AI

The exchange between the father and son was not an isolated moment.

It was part of a story that had begun at home a few years earlier. At the time, I was lecturing in AI art at the National Art School in Sydney, immersed in questions of authorship, authenticity, and machine creativity.

Then my 11-year-old son broke his arm and was suddenly sidelined from sports.

He didn’t want to spend every PE lesson watching from the edge of the field, so we came up with a plan for me to run a series of AI workshops at his school, with him helping.

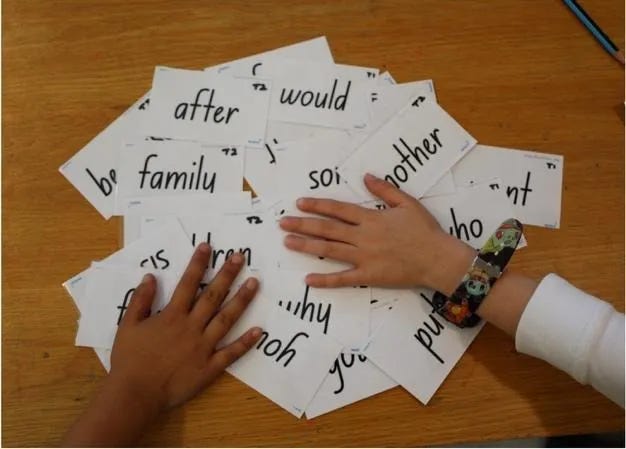

Around the kitchen table, we took the material I was teaching in higher education and translated it for school students, starting with an AI art and literacy pilot for kindergarten.

The idea was simple.

The children turned their weekly spelling words into images using generative tools, then placed them alongside their handwritten originals in a small virtual gallery they could enter using avatars.

On the day of the first workshop, I arrived as the educator. My son arrived as the apprentice, but with a way of moving through the tools that felt different from my own.

As the children created images, he read their excitement, uncertainty, and frustration with an ease I did not yet have. He tested, discarded, and tried again without hesitation, and his responses helped me adapt the program in real time.

I began to see that fluency did not travel in one direction.

I was learning from him.

That shift mattered. In a room where both the educator and the apprentice were experimenting, revising, and discarding, the children did the same. The AI image generator became a working tool in their hands, something they used to extend their ideas into the virtual worlds they were building.

According to the teacher, when the kindergarteners took their next spelling test, the majority performed better.

What stayed with me was how the words had become images in their minds. They were not memorising; they were recalling something they had made, shaped by the way the learning had unfolded.

My son’s arm eventually healed, and he returned to the sporting field.

But the work did not stop there.

It has grown into a larger body of creative AI programs across schools, museums, and galleries, now involving thousands of students each year, alongside professional learning for teachers and museum educators.

While the work has increased in scale, its structure remains the same. Students still begin with the analogue — a drawing, a sentence, a fragment of handwriting. From there, it is carried forward using AI, with authorship remaining firmly in the hands of the student.

In the act of creating with AI, their intelligence is embodied.

Hands move across the paper, heads tilt toward the screen, and attention settles on what feels like theirs. If the machine returns something that does not look right, they waste no time rejecting it.

When the artworks are placed side by side in physical and virtual exhibitions, the emphasis shifts from the finished image to the process that shaped it.

The question is no longer who made it, but how it came into being.

Whose Story Is The Machine Telling?

Working alongside students has led me to think more carefully about how visual narratives are formed. Not simply how images are made, but how stories are inherited, repeated, and contested.

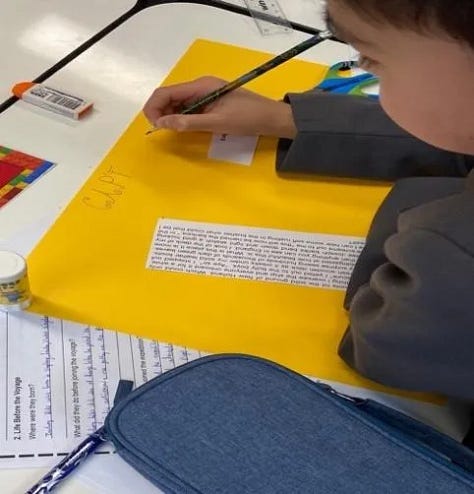

In one project, students worked with historical material and generative tools to translate first-person accounts written from the perspective of real or imagined characters on board Captain James Cook’s HMB Endeavour into short AI-generated films, narrated in their own voices. The technical task was straightforward; the implications were not.

For many students, Cook’s journey was familiar in its most simplified form.

Discovery. Arrival. Naming.

What was less familiar was that this is only one version of events and that, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, the moment of encounter is told from the opposite side of the horizon.

As Senior Gweagal knowledge holder Shayne Williams explains,

My great uncle speaks about how Cook was coming up the coastline.

Our Aboriginal tribes from the south were sending people with message sticks.

They were being tracked all the way up.

In this account, it was Cook who was observed, anticipated, and known before he ever set foot on land. That reversal of perspective is where the students’ understanding began to shift, and it became central to how the AI project was framed.

As First Nations historian Don Christophersen puts it,

You have to listen to both versions of our history.

The Indigenous version and the non-Indigenous version.

They’re both telling the truth, but they’re not the same story.

Using a combination of paper storyboarding and AI tools, they explored ways of moving beyond familiar heroic illustrations of Cook.

They considered what happens when his arrival is viewed from the shoreline as well as from the deck of the ship, and how the image changes when meaning is allowed to emerge from multiple perspectives.

At first, the results unsettled us.

Of course, the machine did not know which story to prioritise. It returned fragments of both. This, too, became part of the lesson. Students saw that AI is not a tool for uncovering truth so much as a system that reassembles what it has been given.

Here, refusal became as important as generation. Students rejected images that reproduced the same heroic tropes they’d grown up with.

This runs counter to what most adults assume: that children passively accept whatever the machine gives them.

These students were harder critics than the adults in the room — quicker to reject what didn’t feel true.

They adjusted language, intervened in visual hierarchies, tried alternatives, and learned that authorship in this space meant making choices and taking responsibility for which stories were allowed to surface.

Gradually, the machine stopped feeling like a device for generating images and began to act more like a mirror, reflecting the structures already embedded in our culture. Students learned to read, shape, and critique the AI, encountering something far older than the technology itself: Representation carries power; prompts frame meaning; and what appears neutral rarely is.

From here, the question of authorship widens away from who made the image and toward whose history it serves.

How Gen-Alpha + AI Is Beyond Our Wildest Imagination

The fear is that AI makes kids passive — sponges absorbing whatever the algorithm serves. That AI will do their thinking for them.

However, from everything I’ve seen, the opposite might be closer to the truth.

Gen Alpha is growing up in a world where machine-learning systems feel ordinary rather than extraordinary. Their attention is on how to work with these tools — sometimes with them, sometimes against them, often around them.

What distinguishes this generation is less technical fluency than a willingness to treat AI as provisional. They test its limits, reject what feels wrong, and understand that rejection is part of the process.

They adapt their outputs until they can recognise themselves again.

In this way, authorship does not recede in the presence of the machine. It emerges through negotiation.

For adults, this is disorienting. We’re used to being the ones who explain technology to children.

Quietly, we are being asked to meet them where they already are, and to recognise that they have begun without us.

Much of our education system is still shaped by a top-down model of expertise.

The teacher knows. The student learns.

In AI contexts, the geometry shifts.

Often, students arrive with instincts, fluency, and confidence that exceed those of the adults in the room. For educators and parents, the task is not simply to instruct, but to recognise when learning must move in more than one direction. This reorientation matters well beyond classrooms.

As I write this, Australia has just introduced the world’s first social media ban for children under sixteen.

It is being framed as an act of protection, and it speaks to the unease many adults feel about what young people encounter through screens, about how attention, identity, and self-worth are forming in environments we do not fully control or understand.

But fear alone cannot be our organising principle.

What matters is learning how to walk alongside children in the world they already inhabit, rather than trying to recover an earlier, pre-digital idea of childhood.

I’m reminded daily that children are not passive consumers of technology. They are creators, curious and selective, forming critical and imaginative relationships with the systems that influence how they see and what they make.

Their first question is rarely “what can the machine do?” It is “what can I do with it?”

I know such agency does not eliminate risk; however, it reframes responsibility.

It reminds us that our task is not to seal children off from the world they are inheriting. Our work is to accompany them through it, to learn alongside them, and to stay open to the moments when they see more clearly than we do.

The father at the exhibition understood this instinctively. His son showed him how something had been made and why it mattered. In that small gesture, a space opened where learning could move in both directions.

About the Guest Author:

Dr Jessica Priebe is an art historian and lecturer at the National Art School in Sydney, and an adjunct adviser in emerging technologies at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia. She founded Artverse Lab in 2022, partnering with schools, cultural institutions, and Indigenous organisations to develop curriculum-aligned AI education programs and immersive online exhibitions.

Thanks, Jing and Jessica. This is such a refreshing take, and great to see real examples of young people critically engaging with AI. It really bothers me when we just assume that they'll passively accept everything, whereas, in actual fact, given the right tools and support, young people are some of the most effective proponents of critical thinking with and without AI.

Such a refreshing air talking about the learning curve from the very pure mindset of our children... Few weeks ago in December a night my 13-yrs old asked a math question which is forgot over time and at that moment a conversation with ChatGPT as a follow-up within few seconds to get the exact answer of my son, and then I asked him how's his impression to today's AI and surprisingly, a teenager's replies as following was impressed: 1) No meaning to help AI to be smarter by giving up and giving in my learning opportunities through Ctrl+C & Ctrl+V, I saw those YouTube videos how teachers to be crazy on their students on those nonsense behaviors; 2) It's helpful to address my concern tonight and I know learning curve as you mentioned so the learning like a mountain climbing, it carries a lot of hard works but meaningful as well; 3) Don't worry too much about me too much and I already know many of those improper behaviors how to engage AI with nonsense, and I could decide how to engage it instead of being controlled by AI. ─ Yes, I admitted as a part of parenting, I paid a lot of attention in daily parenting with children on the youth's behaviors to engage AI, but as the parent, I didn't reflect such deep insights like my son mirroring it in depth a few weeks ago... And in American parenting, children are the mirror to their parents and this evening, I saw an image of myself from my son: 1) Children need guidelines but not limits to engage AI, and the curiosity drives the learning to the higher dimensions of reasoning, and in this process, they do need help and support but non-parenting like asian tiger mom/dad; 2) More patience as called during parenting especially when children made mistakes especially when parents carry good intents but may play a hen's role for protection, it's a fine line between how to let children be grit through mistakes [under control by following the learning curve] and how to help and support the young generations effectively in the back of them; 3) To trust children themselves is to trust parents ourselves since they are the exact mirror 🪞 of our very own, more than meets the eye 👁️ but in the heart-to-heart communications with the youth and in the valuable journey of parenting, we grow up together and in many cases, what may we learn from our children is by far enriched than what may we share to them, or at least 50/50 to learn from each other, in fact it's forever young journey for parenting especially in the era of AI, same as AI is an amplifier of humanity to reflect the adult's world in its mirror, our children are the mirror to reflect the parenting, how we rise up our children in parenting, the exact same way how we engage AI frankly, and in learning process, an infinite learning journey waiting for us in 'every'. ─ As some parenting reflections to share with this topic and a peaceful, mindful, and wonderful 2026! Best,