There’s a curious thing happening with AI shopping assistants.

Tech companies are celebrating explosive traffic growth, thousands of percent increases, while quietly admitting in footnotes that these visitors are far less likely to actually buy anything.

I find this fascinating. I believe both data points are true.

When I shop online w/o AI, the more I click through filters, read reviews, compare products across tabs, the more I want the thing. Each click deepens the desire. It’s like window shopping; the browsing is the pleasure, not just the endpoint.

When I try to tell an AI assistant what I want, it feels, no better word to describe it than exhausting.

Answering its questions, specifying my preferences—I’m doing the work of desire-building myself, describing something I haven’t fully imagined yet. It's opted for efficiency. But I want to wander.

On Monday, I found this book from the 90’s about the American consumer culture called “Land of Desire,” the centre of it revealed a rather unexpected character: the Wizard of Oz.

The Land of Desire

The book started with …

“By the late 1890s, so many goods, in fact, were flowing out of factories and into stores that businessmen feared overproduction, glut, panic, and depression.”

The economy had solved production. With the never-ending scale of expanding, it now faced a different problem: how to make people want things they didn’t know they needed?

The answer was the show window.

The department stores of the late 19th century understood what most AI companies seem to have forgotten: shopping is never about acquiring things, but the experience of wanting them.

Glass was central to the trick. It lets you see everything and touch nothing. The barrier itself created the longing.

There it is. You see it. You can’t have it — unless you go in and pay.

Writers at the time felt the pull.

Theodore Dreiser walked down Fifth Avenue and said, “stirring up in onlookers a desire to secure but a part of what they see, the taste of a vibrating presence, and the picture that it makes.”

While Edna Ferber, a Pulitzer Prize winner, called out a Chicago display, “It boasts peaches, downy and golden, when peaches have no right to be, strawberries glow therein when shortcake is a last summer’s memory.”

The attention reflects an economic opportunity that created the Wizard.

The Wizard of Oz

Among the people who understood this best was L. Frank Baum.

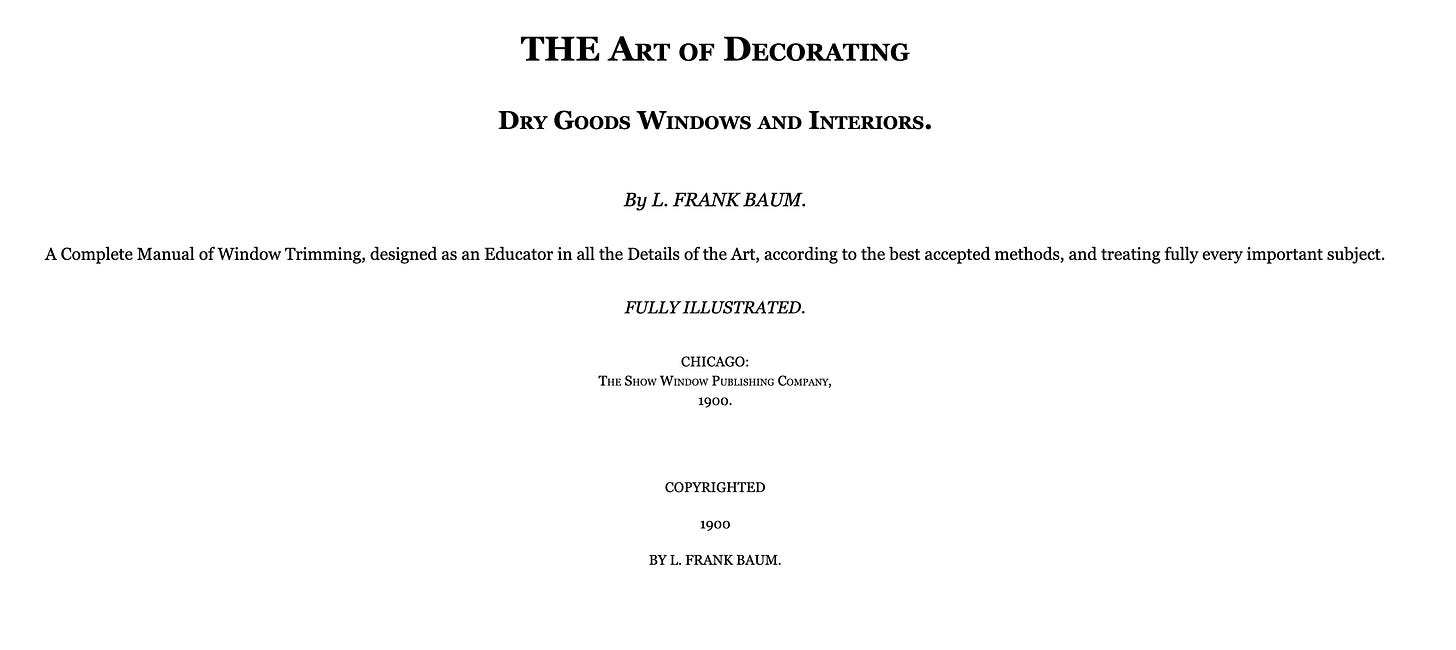

Before the children's books, before Dorothy and the yellow brick road, Baum was a window trimmer. Baum took this principle to its extreme. He founded a magazine called In The Show Window, and he wrote:

He explained what knowledge was needed achieve the best window display:

To make a display of goods in your window that is most attractive, that will sell readily the articles exhibited, is to-day acknowledged an art.

Many things are to be considered. There are the technicalities to be learned, judgment and good taste to be exercised, color harmony to be secured; and, above all, there must be positive knowledge as to what constitutes an attractive exhibit, and what will arouse in the observer cupidity and a longing to possess the goods you offer for sale.”

Baum knew very well that he was in the business of manufacturing want.

Then he wrote a fairy tale about a man who does exactly that.

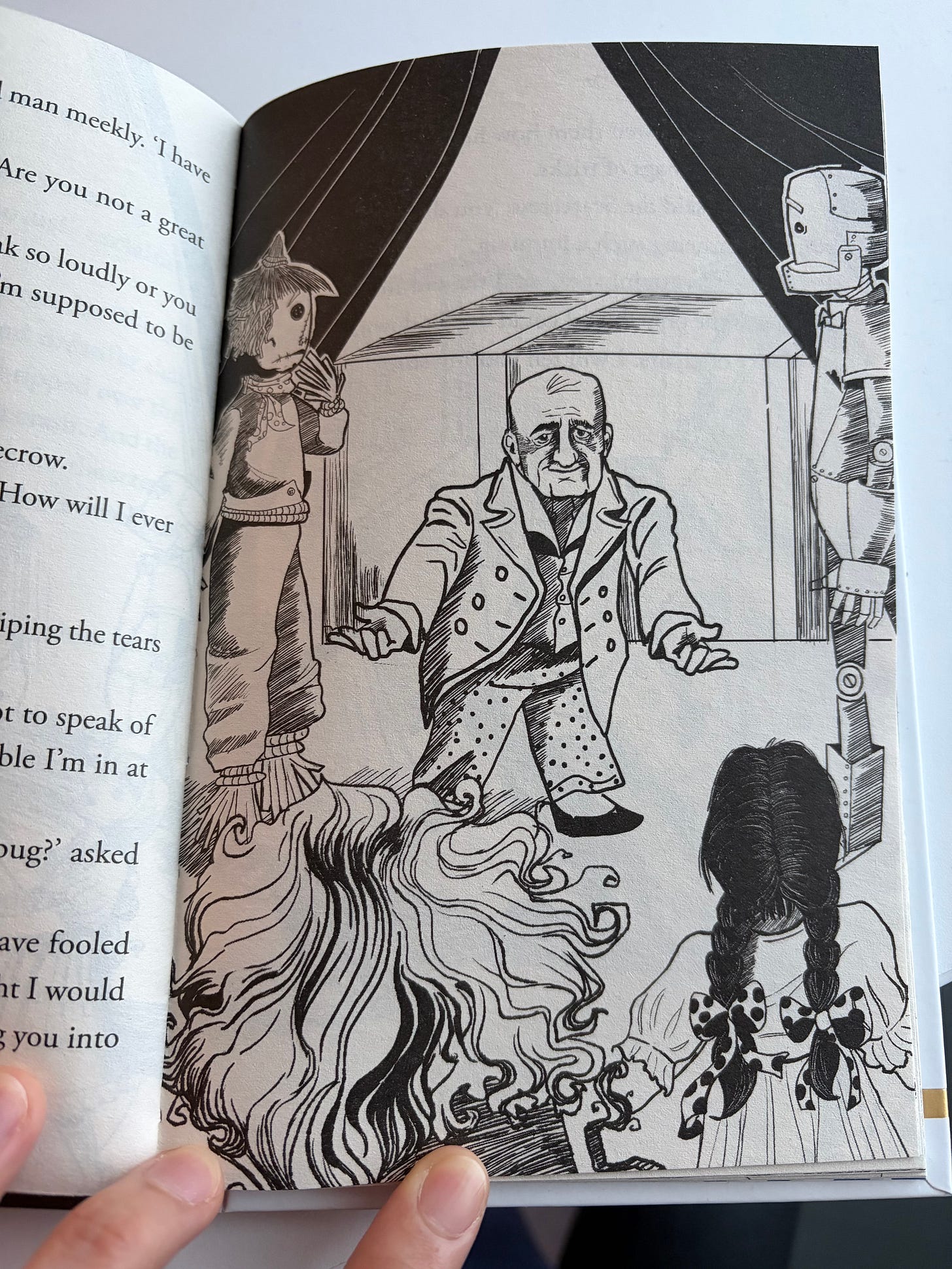

In The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, when Dorothy finally discovers the truth behind the curtain, they found that the Great and Terrible Wizard is a small old man working levers and pulleys.

Every mysterious and even the spooky forms—the floating Head, the beautiful Lady, the terrible Beast— were a smoke, a mirror, an Illusion.

But what matters is that Dorothy forgives him instantly, and the citizens never turn against him. They remember him fondly as the man who “built for us this beautiful Emerald City” (even knowing the whole thing was a trick).

Because even when he leaves in a balloon at the story’s end, the characters got what they wanted anyway. The Scarecrow felt smart, the Tin Woodman felt loved, and the Lion felt brave.

The Wizard has no magic, but the power to tell stories that people buy, which is the only thing that matters…