Hey,

In the time when everyone is expecting/ avoiding an AI bubble.

I thought the combination of macro and tech understanding would help you decide where your investment (portfolio and business) should go in 2026.

So I begged (literally) Klaas Ardinois to put his knowledge into words.

As some of you might be aware, Klaas is my partner in everything.

He spent 20+ years in engineering and 10+ years as a CTO. Klaas has experienced multiple successes and failures in M&A, not to mention boardroom drama that makes Succession seem like children’s play.

Someone with a deep tech background, plus structural investment knowledge, is rare.

But you are about to read his stuff.

BTW, if you are a CEO who is stuck at your AI endeavor, reach out to Klaas.

Enjoy.

Jing

Do you want AI with that?

A friend of mine here in the UK used to say,

AI is like chips.

It’s a play on “do you want chips with that?”

This seems to be the response in every restaurant, no matter what you order.

Chips here in the UK, of course, are chunky fries. As a born & raised Belgian, I am rightfully offended by those fried abominations.

Anyway, so do you want AI with that?

Everywhere I turn, it seems shoved in my face.

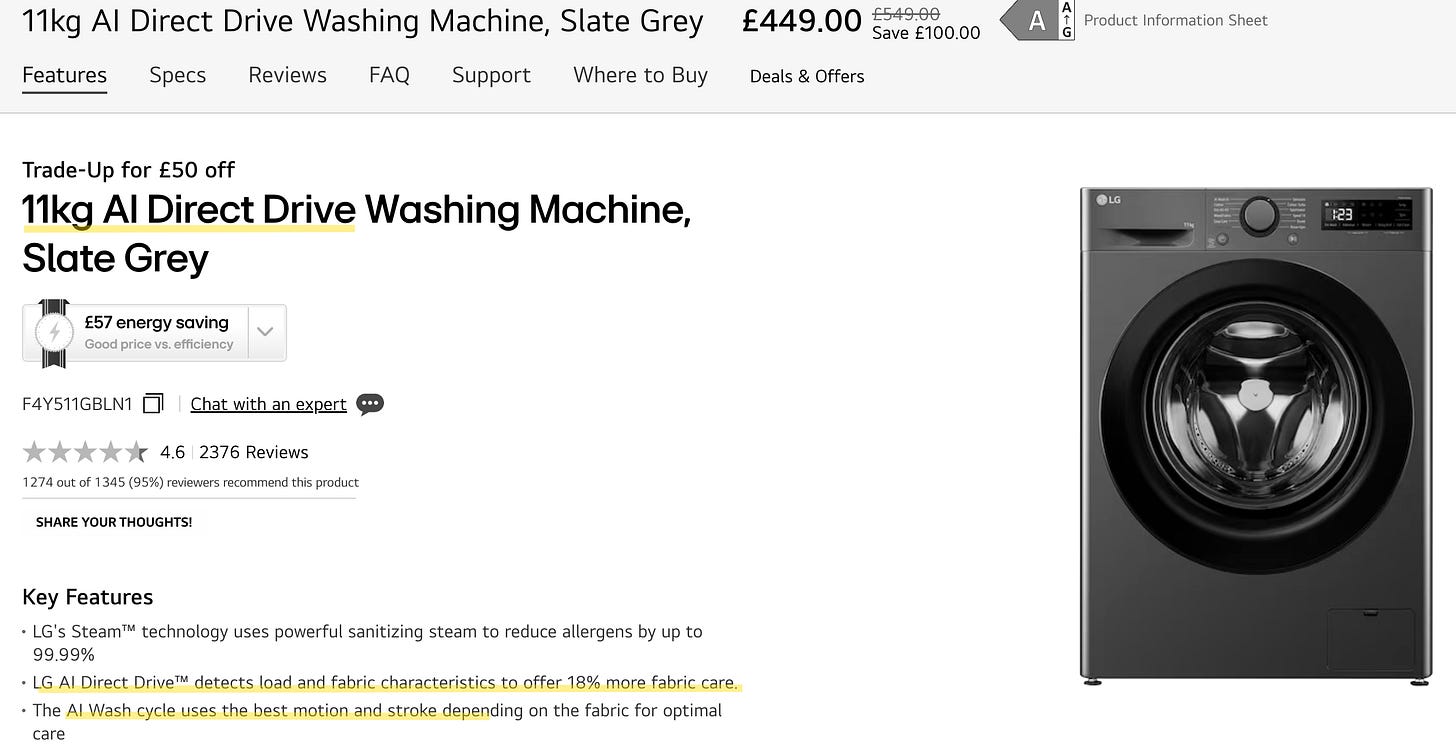

The AI DD™ combines deep learning technology with 7 Motion Direct Drive to analyze fabric types and optimize washing cycles.

Yes...that is really an LG washing machine. Here’s a short about the machine.

I wish I could make this stuff up.

But this isn’t the appliances section of Builder Magazine, so let’s move on.

Before we dive into the investing part, let’s agree on one thing, though.

The value of the technology is not the same as the valuation of companies in the ecosystem. So this is a piece of thinking about Nvidia, market dynamics, and expectations. Regardless of how useful AI (washing machines and otherwise) may end up being.

Your Neighbour Uses ChatGPT. So What?

Before we go any further, let’s get one thing straight.

Your auntie discovered ChatGPT last Christmas. Your neighbour uses it to write emails. Cool. AI is useful.

But that’s not what moves Nvidia’s stock price.

The value of the technology is not the same as the valuation of companies in the ecosystem.

Nvidia’s valuation is built on expectations — specifically, how many AI chips giant companies will buy next year, and the year after that.

So when people ask “is AI a bubble?”, that’s the wrong question. The real question is: will companies keep spending billions on chips at the rate Wall Street expects?

That’s what this piece is about. Nvidia, market dynamics, and expectations. Not whether AI washing machines are useful.

The video version here (will be released on the following Wednesday):